How do faith communities dedicated to justice sometimes become spaces of deep harm? Why do churches that claim to resist power still concentrate it in ways that silence dissent?

For many, finding a faith community that takes justice seriously can be life-changing. Some churches boldly challenge capitalism, racism, and colonialism. Others embrace LGBTQ+ inclusion or economic redistribution, offering a prophetic vision of the world. These commitments can make a church feel like home, a place where faith and liberation are intertwined. The reality, however, is rarely so binary. Most communities contain elements of both liberation and control—sometimes in the same practice, program, or person. This complexity is precisely what makes navigation so difficult: the same spaces that offer genuine healing and connection can simultaneously harbor harmful dynamics that resist examination.

What happens when a church that preaches justice fails to practice it internally? What if the very spaces that claim to reject hierarchy, oppression, and coercion instead replicate those same dynamics under a different banner? How do we distinguish between communities that embody liberatory praxis and those that merely perform it?

I've spent over twenty years navigating progressive and radical Christian spaces—from post-evangelical experiments to Catholic Worker communities, from institutional mainline settings to DIY spiritual collectives. In that time, I've experienced both authentic attempts at liberationist spirituality and sophisticated control mechanisms dressed in progressive language. The patterns I've observed transcend theological differences, appearing wherever power concentrates without accountability.

This exploration isn't merely academic—it's deeply personal. For fifteen years, I led (in an awkward anarchistic sort of way) a Christian intentional community that struggled with these very tensions. We aspired to build a high-commitment, anti-authoritarian space where liberation wasn't just preached but practiced. Honestly, our results were a mixed bag. Despite our best intentions, we sometimes reproduced the very power dynamics we sought to dismantle. This experience taught me the profound difficulty of creating truly horizontal structures within a religious landscape designed for hierarchy.

I've also stood on the receiving end of religious authoritarianism—from my formative years in charismatic churches where 'anointed leadership' functioned as spiritualized control, to more recent experiences with progressive communities like Church of All Nations, where justice language masks deeply problematic power structures. These experiences have left me with both scars and insights about how control operates in spaces that claim to resist it.

This essay is for those who are beginning to question their church's leadership, those who have left after experiencing harm, and those who have supported a justice-oriented church but are now uncertain about its internal ethics. It offers language for understanding what happens when a faith community becomes high-control, insights from cult studies, and resources for healing and accountability.

While authoritarianism in fundamentalist churches is widely recognized, the ways power operates in progressive faith communities are less often examined. This essay explores how churches that claim to resist hierarchy and oppression can, paradoxically, replicate these same dynamics under the banner of justice. My goal is to illuminate common patterns that appear in religious groups—even those committed to challenging oppression—where power becomes concentrated and dissent is punished.

Unlike fundamentalist churches, which openly enforce hierarchy and obedience through strict doctrine and top-down authority, high-control progressive churches often operate through informal yet powerful social mechanisms. Instead of demanding submission to a rigid creed, they require adherence to an evolving set of ideological commitments determined by leadership with performance of those commitments judged by that leadership. Instead of explicit punishments, they use social exclusion, shame, and accusations of ideological impurity to enforce conformity.

Throughout this analysis, I'll draw on what might be called an 'ecology of control'—examining how high-control religious spaces create interlocking systems that constrain members' autonomy while making that constraint feel divinely ordained. This framework helps us understand how different tactics—from weaponizing scripture to selectively applying justice principles—work together to create environments where questioning becomes nearly impossible. By mapping these patterns, we can better understand how spaces designed for liberation sometimes become sites of subtle captivity.

If you are experiencing disillusionment, confusion, or fear in questioning your church's leadership, know this: you are not alone, and your concerns are valid. More importantly, the cognitive dissonance you're experiencing—that uncomfortable gap between stated values and lived reality—isn't evidence of your spiritual immaturity. What if you took the risk of assuming you're wiser than you think, and that dissonance is trying to tell you something?

The urgency of this conversation cannot be overstated. As Trump’s second term emboldens Christofascist movements, the role of churches as sites of resistance becomes more critical than ever. But for churches to function as liberatory spaces, they must first examine their own internal power dynamics. Otherwise, they risk becoming microcosms of the very authoritarianism they claim to oppose.

Spaces of genuine spiritual resistance are essential—not luxury. Communities committed to liberation need internal structures that foster the very freedom they seek externally. We cannot effectively counter authoritarianism in society while reproducing it in our sacred spaces.

What's at stake isn't just individual healing, though that matters profoundly. At stake is our collective capacity to sustain liberatory movements through the difficult days ahead. High-control religious environments don't just harm individual members—they undermine our broader struggles for justice by depleting the very resources those struggles require: trust, solidarity, and the capacity for principled dissent.

My aim is threefold: to validate the experiences of those questioning harmful dynamics in their spiritual communities, to offer conceptual frameworks that make sense of disorienting abuse, and to sketch possibilities for building truly liberatory spiritual spaces that can sustain us through the work ahead. The path forward requires both unflinching critique and generous vision—both naming what's broken and imagining what could be.

Recognizing the Patterns of High-Control Churches

Not all churches that present as justice-oriented actually operate in a way that fosters liberation. Some churches use justice language as a tool of control, enabling abuse and harm in secret while extoling the opposite in public.

Here are some warning signs that a faith community may be functioning as a high-control environment rather than a healthy spiritual home.

I. A Growing Gap Between Public Messaging and Private Practices

A church might publicly champion liberation and justice, speaking out against oppressive systems in society. However, if it maintains hierarchical, coercive, or secretive leadership structures internally, this is a major red flag.

In high-control churches, there's often a significant disconnect between public image and private reality. Some communities produce brilliant analyses of systemic injustice while maintaining internal practices that contradict their stated values—whether through financial arrangements that benefit leadership, decision-making processes that exclude marginalized voices, or accountability structures that protect those in power.

A justice-oriented church should be willing to apply its own critiques to itself. If it demands accountability from the world but resists any internal scrutiny, it is more invested in image than integrity.

II. Increased Requirements for Loyalty as You Move Closer to Leadership

Many high-control churches appear open and welcoming at first, allowing room for curiosity and questions. However, the deeper someone moves into leadership, the more conformity and loyalty are expected. This creates what cult researcher Janja Lalich calls "bounded choice"—a phenomenon where all decisions are shaped by an institution's ideology, making questioning feel impossible. Members' choices are limited to those sanctioned by the group, giving the illusion of autonomy while enforcing conformity.

This might look like:

Leaders testing members' willingness to conform by gauging their reactions to certain teachings or decisions. This might include subtly introducing controversial beliefs in private settings to see how members respond before they are trusted with greater leadership responsibilities.

Subtle pressure to align with leadership in personal and theological beliefs. Members may initially be told there is room for diverse perspectives, but as they become more involved, they experience increasing pressure to adopt the leader’s exact interpretations of theology, justice, or spiritual practice.

Framing dissent as dangerous, immature, or a sign of personal failure. Those who express doubts or disagreements may be warned that they are "not ready for leadership," lack spiritual maturity, or are being influenced by external forces (such as individualism, capitalism, or whiteness).

Loyalty to the leader or core leadership group being treated as equivalent to loyalty to God, justice, or the movement. Members may hear messages like, "To question this vision is to work against God's plan," or, "If you leave, you're abandoning the work of liberation."

Expectations of increasing personal sacrifice as a demonstration of commitment. As members rise in leadership, they may be expected to take on unpaid responsibilities, give more of their time and resources, or structure their personal lives around the needs of the church—sometimes at the expense of their own well-being.

Dismissing or downplaying external sources of wisdom. Members may be discouraged from seeking outside theological education, reading certain books, or engaging in relationships outside the community that might challenge leadership’s authority.

Creating a false sense of urgency that discourages reflection. Leaders may emphasize that "now is a crucial moment in the movement" or that "we are on the frontlines of spiritual and social change," making any questioning of leadership feel like a distraction or betrayal.

Gradually isolating leadership figures from external accountability. As someone moves deeper into leadership, they may find that they are encouraged to rely solely on the church community for support, distancing them from relationships and networks that might provide alternative perspectives.

A shifting, unspoken hierarchy where some voices matter more than others. While the church may claim to be communal or non-hierarchical, those who are seen as more loyal or compliant may be given access to key decisions, while those who express skepticism find themselves subtly excluded.

I've witnessed communities where new attendees were welcomed with genuine warmth and openness, only to discover as they moved deeper into the inner circle that leadership expected increasing conformity. One person described it as "an onion in reverse"—the closer you get to the core, the more rigid the expectations become.

If disagreement is treated as disloyalty, the church is likely operating with authoritarian tendencies rather than true communal discernment.

I want to clarify something: It’s natural for organizations—including churches, activist groups, and justice-oriented communities—to expect a certain level of alignment from their leadership. Those in positions of responsibility should uphold the mission, values, and collective commitments of the group.

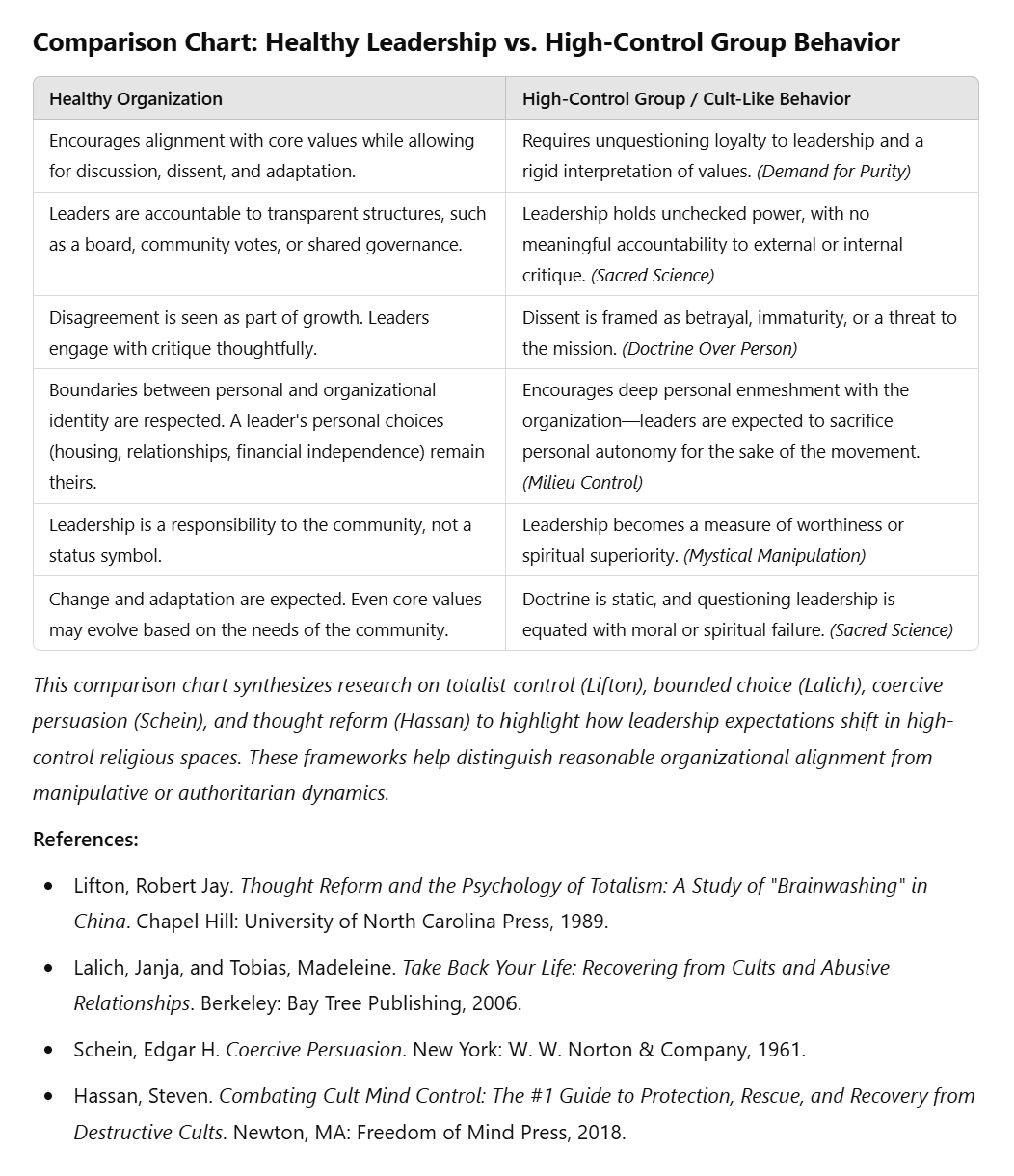

However, in high-control environments, this expectation shifts from shared responsibility to enforced conformity. Instead of fostering collaborative alignment, these groups demand unquestioning loyalty to leadership and rigid ideological adherence. The key difference lies in how alignment is cultivated and enforced: in healthy organizations, discussion and evolution are encouraged; in high-control groups, dissent is punished, and questioning leadership is reframed as betrayal.

The chart below highlights these distinctions.

III. Weaponizing Scripture to Suppress Criticism

One of the most common tactics in high-control churches is the misuse of Matthew 18, which discusses handling conflicts privately before bringing them to the community. While this passage can be useful for personal disputes, it is not meant to shield leadership from accountability.

What begins as Jesus' teaching on reconciliation transforms into an institutional weapon that silences victims and protects perpetrators. The bitter irony is almost too perfect: a passage about community accountability repurposed to prevent exactly that.

This selective biblical application conveniently ignores that Jesus positions this teaching within a chapter that begins with him placing a child among the disciples and warning that anyone causing "little ones to stumble" would be better off thrown into the sea with a millstone around their neck. The first priority is protection of the vulnerable, not institutional reputation or leadership comfort.

The weaponization typically follows a predictable script:

Forced privacy: "Did you speak to them privately first?" becomes the immediate response to any critique of leadership, regardless of power dynamics or the nature of the harm. This privacy requirement functions effectively to isolate critics and contain damaging information.

Process fetishization: The "proper channels" become more important than the content of the concern. The steps of Matthew 18 are transformed from a pathway to reconciliation into procedural hurdles designed to exhaust dissenters long before any community involvement.

False reconciliation: The goal shifts from accountability to "restoration of relationship," which in practice often means pressuring harmed individuals to forgive without any meaningful change or justice. The language of "reconciliation" becomes a sophisticated form of spiritual bypassing.

Selective invocation: Notice how these same leaders rarely insist on Matthew 18 procedures when publicly criticizing other churches, political figures, or cultural institutions. The "biblical process" only applies when their own power is questioned.

When a church's leadership responds to serious allegations by invoking Matthew 18 while simultaneously rejecting accountability structures, they reveal their theological sleight-of-hand—scripture as shield, not guide. They're not concerned with biblical faithfulness so much as maintaining control over who gets to speak and who must remain silent.

A church genuinely committed to liberation will welcome scrutiny, not suppress it. It will recognize that accountability isn't a threat to mission but essential to it. Most importantly, it will understand that the goal of Matthew 18 was never institutional reputation management, but the creation of communities where harm is addressed openly and the vulnerable are protected fiercely.

IV. Selective Application of Justice Principles

A church may speak boldly against empire, capitalism, and white supremacy while maintaining rigid hierarchy, financial control, or oppressive leadership within its own walls. The language of justice should be a tool for transformation, not a shield for authoritarianism. When a church weaponizes justice rhetoric to suppress critique, it risks becoming the very system of control it claims to resist.

Excusing Authoritarian Leadership: A movement is not beyond critique simply because it fights for justice. Some churches position their leadership as uniquely enlightened, anointed, or indispensable to the movement. This happens when leaders demand unquestioning obedience, dismiss dissent as divisive or harmful, and centralize decision-making without meaningful transparency or accountability. In some churches, authoritarianism is built around a single charismatic figure, while others operate as insular collectives where loyalty determines who holds power.

Dismissing Concerns as “Capitalist Individualism”: Many churches challenge capitalism’s emphasis on hyper-individualism and isolation. However, in high-control spaces, this critique is distorted to justify coercion—framing healthy personal boundaries, questioning leadership, or leaving the church as selfish or disloyal. This happens when personal autonomy is demonized, such as when members who set boundaries—whether by declining unpaid labor, making independent decisions about their family, or choosing to leave—are accused of abandoning the community. Leaving the church is framed as a failure of faithfulness rather than a neutral choice, and those who go are labeled as prioritizing personal comfort over commitment. In some churches, collectivism is used as a form of control, where members are expected to sacrifice personal agency for the greater good rather than engage in mutual support.

Creating False Binaries Between Different Forms of Oppression: A truly liberatory church recognizes that systems of oppression are interconnected. However, high-control churches often pit justice movements against each other to silence critique, deflect accountability, or justify inaction. Some common false binaries include:

"Feminism is a distraction from more pressing justice issues." Churches that focus on racial or economic justice often downplay gender oppression, suggesting that feminism is secondary or divisive. Women, nonbinary people, and trans people are told to "be patient" or "prioritize the bigger struggle," reinforcing patriarchy within so-called radical spaces.

"We support racial justice, but LGBTQ+ issues are too divisive." Some churches claim to fight white supremacy while rejecting queer inclusion as optional or unnecessary—even though queer and trans people of color exist and deserve full participation. LGBTQ+ concerns are dismissed as "Western distractions," even when the community has queer members seeking affirmation.

"Economic justice comes first; identity politics are a distraction." Churches that emphasize class struggle often downplay the impact of race, gender, or sexuality, claiming that focusing on "identity" dilutes the fight against capitalism. This ignores how capitalism itself is racialized and gendered, disproportionately harming people of color, women, and LGBTQ+ communities.

"Challenging white-led churches is divisive; we should focus on unity." Predominantly white churches may claim to support anti-racism while resisting any structural change. When members push for reforms—such as shifting power, hiring more BIPOC leaders, or confronting institutional racism—they are told to stop "sowing division." Unity is framed as more important than dismantling white supremacy.

"To challenge a progressive leader is to undermine the movement." In justice-oriented churches, there is often a reluctance to challenge charismatic leaders, especially if they have done important work. White-led and BIPOC-led churches alike may protect their leaders by framing internal critique as betrayal—regardless of whether the issue is financial misconduct, spiritual abuse, or silencing survivors. The idea that a leader’s past contributions excuse present harm is a common way to suppress accountability.

By rejecting false binaries, churches can move beyond performance-based justice work and actually embody the liberation they claim to seek.

V. Dissenters Are Silenced, Ostracized, or Reframed as "Maladjusted"

When people leave or challenge leadership in a high-control church, their departure is rarely treated as a neutral decision. Instead of addressing legitimate concerns, church leaders often reframe dissenters as bitter, unstable, or wayward.

This pattern serves multiple purposes: it discredits the person speaking out, deters current members from questioning leadership, and ensures that the church’s internal narrative remains intact. Rather than reckoning with hard truths, the church rewrites history to cast itself as the victim of malicious attacks by disgruntled former congregants.

Common tactics include:

Labeling former members as emotionally unstable. Those who raise concerns are framed as angry, irrational, or mentally unwell, rather than as people with valid experiences of harm.

Encouraging members to sever friendships with those who leave. Current members are told that former members are spiritually dangerous, leading to abrupt and painful social isolation for those who depart.

Questioning motives rather than engaging with substance. Leaders claim that dissenters are acting out of personal grievance, jealousy, or unresolved trauma, shifting focus away from the actual harm they experienced.

Focusing on tone rather than content, method rather than meaning. Rather than engaging with the substance of concerns, leaders focus on how concerns are communicated, privileging etiquette over ethics.

This dynamic aligns with Steven Hassan’s BITE model of high-control groups, specifically in its information control component: by limiting access to outside perspectives (including those of former members), the church prevents current members from evaluating leadership critically. The less members hear from those who left, the easier it is to maintain the illusion that leadership is beyond reproach.

This pattern is not unique to fundamentalist churches. Even in progressive religious spaces, dissenters may be dismissed—not as heretical or rebellious, but as "toxic," "uncharitable," or engaging in "call-out culture." Justice-oriented institutions may use different language to defend leadership, but the end result is the same: internal critique is framed as betrayal, and those who raise concerns are cast as problematic rather than heard.

A healthy community allows people to leave without stigma, treats concerns as opportunities for reflection rather than threats to leadership, and maintains relationships across differences rather than using social pressure to enforce conformity.

VI. Personal Decisions Are Subject to Leadership Oversight

One of the defining features of high-control religious groups is their tendency to extend authority beyond theology into members’ personal lives. This can happen subtly—through cultural norms and unspoken expectations—or explicitly, through direct interference in personal decisions.

This might include:

Expecting members to seek approval before making personal decisions. Some churches require members to consult leadership before dating, moving, taking a job, getting married or other major life changes.

Creating financial or housing dependency. Members may be encouraged to live in church-owned housing, work for church-affiliated businesses, or enter financial arrangements that make leaving difficult.

Pressuring individuals to conform in gender identity, mental health decisions, or relationships. This might look like discouraging therapy unless it aligns with church-approved perspectives, pressuring members to stay in unhealthy marriages, or pushing a rigid framework of gender roles.

This level of oversight is often framed as pastoral care, mentorship, or spiritual formation. Leaders may claim that deep community requires deep trust, or that submission to the wisdom of elders is a sign of humility. However, there is a difference between genuine guidance and coercive control.

A healthy church offers support without demanding obedience, respects the personal autonomy of its members, and allows individuals to make their own choices without fear of social or spiritual consequences.

Navigating Doubt, Departure, and Accountability

Recognizing harmful patterns in a religious community can be profoundly disorienting. The realization that a church—especially one deeply committed to justice—may be operating in ways that replicate the very power structures it critiques can create deep internal conflict. Those who begin to question may feel isolated, uncertain, or afraid of what comes next.

For those still within a high-control church, doubt may feel like betrayal. For those who have left, the transition can bring grief, confusion, and a loss of identity. For those who have supported the church from the outside, allegations of harm may be difficult to reconcile with the positive work the community has done.

Yet questioning, leaving, or holding an institution accountable does not mean rejecting faith, justice, or community itself. It is an act of integrity. Whether you are still inside, navigating the trauma of departure, or wrestling with what accountability looks like from the outside, this section offers clarity for the road ahead.

I. For Current Members: Why Questioning Feels Like Betrayal

If you are still in your church but beginning to have doubts, you may feel torn between the good you’ve experienced and the discomfort growing inside you. This cognitive dissonance—that tension between stated values and lived reality—is not a sign of disloyalty or spiritual immaturity. It is a sign that your critical faculties are functioning.

Many high-control religious spaces create an all-or-nothing loyalty test where questioning is equated with betrayal. They may frame doubt as:

A sign of spiritual immaturity or rebellion.

A failure to grasp the bigger vision.

Evidence of corruption by individualism, whiteness, capitalism, or some other external influence.

These tactics are designed to make you distrust your own instincts. High-control groups often employ thought-stopping techniques that make independent thinking difficult, leaving members feeling isolated or guilty for questioning leadership. If discomfort arises when raising concerns, it is worth examining whether that discomfort is due to personal uncertainty—or because the church has conditioned members to view dissent as dangerous.

A healthy community allows for critique without equating it with disloyalty. If raising concerns leads to fear, shame, or social exclusion, it is worth asking whether this is truly a liberating space.

II. For Former Members: The Trauma of Leaving

Leaving a high-control church often results in deep emotional, psychological, and social upheaval. It is common to experience:

Guilt – "Was I the problem?"

Confusion – "Why didn’t I see the harm sooner?"

Isolation – "Why did my friends suddenly stop talking to me?"

Fear – "Will speaking out make things worse?"

These feelings are not signs of personal weakness—they are predictable consequences of leaving a high-control religious environment. Spiritual abuse and coercive control leave real psychological and physiological impacts, and the recovery process can take time.

Steven Hassan’s BITE model helps explain why leaving feels so disruptive. Many high-control churches regulate behavior, limit access to information, discourage critical thinking, and enforce conformity through guilt and fear. When leaving, former members often experience:

Disruption of life structure – If the church controlled major aspects of daily life, leaving may mean losing housing, employment, or social networks.

Cognitive dissonance – Thought control mechanisms make it difficult to reconcile past beliefs with present realities.

Emotional fallout – Fear, shame, and guilt often surface even after one recognizes the harm.

Social isolation can be one of the most painful aspects of leaving. Many former members find themselves ostracized, gradually excluded from gatherings, and treated as dangerous influences by those who remain. This pattern is not accidental—it serves both as punishment for the one who left and as a warning to those who might consider leaving.

Leaving a high-control church is not a failure—it is an act of courage. Over time, many former members find that stepping away creates space for healing, critical reflection, and the rebuilding of identity. The process, often referred to as religious recovery, involves developing new meaning systems, reconnecting with personal agency, and forming healthier relationships outside of the church’s control.

Healing is not linear, but it is possible. Many who leave high-control religious spaces find that over time, they regain a sense of autonomy, critical thought, and connection outside the group’s influence.

Note: I am currently conducting thorough research to identify reputable resources that support individuals recovering from high-control religious environments. I will update this essay with specific recommendations once I am confident in the quality and appropriateness of the resources I share.

III. For Outside Supporters: When Justice Language Masks Harm

Those who have supported justice-oriented churches from a distance may feel conflicted when allegations of harm emerge. These communities often speak prophetically on important issues and fill crucial gaps in the religious landscape. The instinct to defend them, or to assume that criticisms are exaggerated, can be strong. However, justice-oriented language should never be used as a shield against accountability.

Harmful systems persist when people prioritize institutional preservation over human well-being. Many of the signs of ideological totalism, identified by Robert Jay Lifton, appear in progressive religious spaces, including:

Mystical Manipulation – Leaders position themselves as uniquely anointed interpreters of justice, making critique seem like an attack on the movement itself.

Demand for Purity – Questioning leadership is equated with moral or spiritual failure, creating impossible standards where only those who conform are considered mature.

Sacred Science – The community’s ideological framework is treated as unquestionable, turning justice concepts into tools of control.

Doctrine Over Person – Individual harm is dismissed in favor of protecting the movement’s reputation, treating people as expendable for the greater cause.

When allegations of harm surface, there is a choice to be made: will we prioritize the image of justice work, or justice itself? Holding beloved institutions accountable can be painful, but justice cannot be selectively applied. Communities that claim to fight oppression should not be excused when they perpetuate harm.

Justice work must be ethically consistent. A movement cannot claim to resist oppression while replicating the same coercive tactics it denounces elsewhere.

Moving Forward: A Vision for True Liberation

A church committed to justice must be accountable, transparent, and open to critique. The measure of liberatory work is not found in eloquent analysis but in the lived reality of those affected by its practices.

For those who have left high-control religious environments, healing is possible. The process may be slow, but disentangling from systems of coercion makes space for something deeper: a spirituality that is chosen, not imposed.

For those still within such communities, the fear of questioning is not a sign of betrayal—it is a sign of awakening. Discomfort is not failure. It is often the first signal that something sacred within you is resisting control.

For those who have supported justice-oriented churches from the outside, accountability is not an attack—it is an act of care. Movements that refuse self-examination will eventually collapse under the weight of their own contradictions. True justice work requires ethical consistency: a willingness to apply our most radical commitments not only to the world, but to ourselves.

A truly liberatory community will not suppress dissent, demand rigid conformity, or shield leadership from critique. It will encourage questions as a sign of integrity. It will distribute power rather than hoard it. It will cultivate trust rather than enforce obedience. And it will make room for those who leave, knowing that freedom means giving people the space to choose.

Healing is possible. Trust can be rebuilt. The world we long for begins not in grand declarations but in the quiet, persistent practice of making room for each other’s questions. Liberation is not a theory—it is something we must live, together.